Over the years I have spoken to hundreds of potential clients interested in corporate history books. Nearly all understood that there is a difference between history and public relations, but few seemed to know what it was. One company even got a proposal from me, handed it over to its PR team, and came back later disappointed with the result—but not sure why. It was perspective that was lacking.

Among the things that good historians can bring to corporate history books that no one else can is the ability to put things into a broader context, adding dimension and depth to the story of a single firm. That requires two things often lacking in the corporate suite: the willingness to spread the credit beyond the organization, and the inclination and ability to take a hard look at the organization from the outside in as well as from the inside out.

Putting your company story into historical perspective is not easy, but it brings great benefits. Context can breathe life into founding legends, cast a new light on corporate successes and failures, and help readers recognize the familiar in the past.

“You Didn’t Build That”

When Barak Obama told an audience in Roanoke Virginia that “If you’ve got a business . . . you didn’t build that,” he was skewered, and rightly so. It was a surprisingly inept speech from a usually adept speaker. But if you look at the words surrounding that unfortunate phrase you see not a denial of the value of entrepreneurship but a plea for consideration of context in corporate history, that success depends on things beyond the business, like infrastructure, the internet, and good government.

If Obama erred in one direction, most amateur corporate historians err in the other: painting corporate leaders as unfailingly courageous, uncommonly capable, and singlehandedly responsible for success or failure. Indeed, some corporate history books are even structured on a “one chapter per CEO” basis. Not only is this a staggering failure of imagination, it also papers over underlying contextual shifts that can be far more important than the personal qualities of individual leaders.

Apple Macintosh, 1984

In the context of the mid-1980s, for example, when Apple lost its battle with Microsoft to control the PC market, Steve Jobs came off as an ineffective executive. Twenty years later the CEO who failed to see the importance of open architecture was hailed as an iPhone visionary. But in truth only the context changed. In both cases Jobs insisted on integrating hardware and software.

Perspective does not always get squeezed out of the C-Suite—in rare cases an entire corporate culture has been built upon recognition that it was context more than commercial savvy that led to success. While I was researching my history of the engineering consulting firm MPR Associates for my book Sustaining Excellence, it became clear that the company’s three founders “didn’t,” in Obama’s words, “build that.” Instead they had adopted a corporate culture and an engineering consulting model wholesale from the United States Nuclear Navy. Admiral Hyman Rickover, who had never served in the company was as much a founder as anyone. MPR, to its credit, was glad to acknowledge that debt.

Taking the Outside View

I have known of corporate historians whose expectations regarding sources were pretty low. Give them some annual reports, scrapbooks, some internal papers and photographs, and a few oral history interviews and they could produce a passable story. But clients deserve better, and a good historian should be driven to provide it. The client relationship and use of internal records all push an author to take a particular perspective—that of looking from the inside the company out.

There are hazards to this approach. First is the problem of evidence—how do you know that a particular story, told over and over again in company publications is entirely accurate? In the case of one professional organization that I worked for, its first “historian” more than a century ago, had gotten the sequence of events leading up to the founding wrong. That sequence was passed down—incorrectly—for nearly 150 years. How is the historian to know?

When I take on a project, I begin with a look from the outside in, starting with a review of books and articles about the particular business, discipline, or specialty in question. I then pivot to an in-depth newspaper search about the corporation. In doing so I help inoculate myself from buying uncritically into legend and lore that may have long ago come untethered from fact. In the case of the professional association’s founding sequence, it seemed “off” to me, so I dove into my 150-year-old newspaper collection and figured out what really happened.

There are even greater consequences when the corporate historian never decamps from inside company walls. Competitors might be overlooked, demonized, or worst of all, not recognized for their contribution to the overall business. Particular corporate initiatives may be chalked up to “innovation” or a mere whim when they actually resulted from a competitor’s insight or even regulatory change. There was a time when internal company records like annual reports and board of directors meeting minutes laid out the motivations for business decisions in some depth and detail. In the post-World War II era, however, that candor slowly evaporated so that internal sources are often guaranteed to provide only a partial picture at best or to mislead at worst.

Challenging Founding Legends

Most corporations cling to a bold, all-caps, less-than-paragraph length founding legend that inevitably revolves around a word like vision. Not to discredit those entrepreneurs who have truly been uncommonly foresighted, but in many cases business enterprises begin with a good idea, a willingness to take risks, and a context which minimizes the hazards to the point that the business can succeed.

I have written corporate history books for two of the great long-haul trucking pioneers, Consolidated Freightways, and Roadway. Only the former fits the “up from the bootstraps” narrative preferred by the writers and consumers of corporate history. Leland James progressed from lone trucker to CEO of Consolidated Freightways because he was one of the first to the field in the thinly settled Pacific Northwest where, despite the delays caused by bad roads, he could still provide faster service than the railroads.

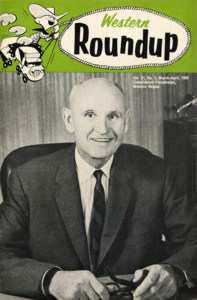

Leland James of Consolidated Freightways

Roadway’s Galen Roush on the other hand, lived a much different story. Roush never drove a truck, and by the time he started business in the 1930s the nation’s industrial heartland was crisscrossed with good roads and trucking startups. It was context that provided Roush with his advantage, for he started out in Akron, Ohio, home to the world’s largest rubber manufacturers. Firestone and Goodyear diverted their loads from trains to trucks despite the higher shipping costs in order to burn up more tires and thus build their own businesses.

The Consolidated Freightways founding story may be more conventional than Roadway’s, but later developments in its corporate history show how attention to context can make past accomplishments all the more interesting. In the expansive western states where Consolidated Freightways operated it was essential to haul as much load as possible. The states though, influenced by railroads and seeking to protect their pavement, put strict length limits on trucks. In 1940 Consolidated Freightways manufactured one of the first practical cab-over-engine tractors in order to get around this contextual hurdle. These allowed additional freight to be carried where the hood of the truck used to be. Consolidated Freightways no longer survives, but its manufacturing offshoot, Freightliner, is now one of the world’s leading truck manufacturers.

In these cases, as in so many others, contextual factors like these were well-known to company old-timers and most writers would surely mention them as being important. But in line with the writer’s dictum “show, don’t tell,” whenever possible I build these contextual substories into the corporate history itself so that the reader is just not told, but experiences through description just how much of an obstacle state length limits were or how much an advantage being located in the tire capital of the world could be.

The Familiar and Fascinating in a Relived Past

This, in the end, is the greatest advantage of maintaining a wide sense of perspective in writing corporate history books. Lived experience takes place on a broad stage, becoming ever more complex due to endless encounters with unexpected things. Relived experience (that is, history) must offer the same kinds of encounters if it is to come to life in the mind of the reader.

Most writers understand this and so make sure to include “history” in their accounts. Worst case efforts, which I encounter all too often, shrink the stage and turn the history into mere props. A paragraph might begin by evoking the “Gay Nineties” or the “Great Depression” in a few predictable stereotypes before pivoting back to the internal company story with no indication of how or why those larger landmarks mattered.

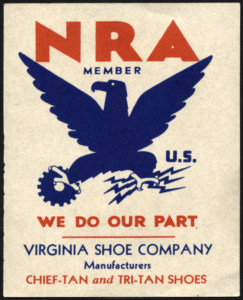

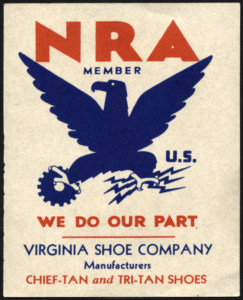

The Blue Eagle was issued to firms that complied with the New Deal’s “Codes of Fair Competition.”

If you know your context, you know that seemingly abstract national stories do matter. You can show your reader how they mattered rather than simply include them as so much window dressing. For example, one of the earliest federal initiatives of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was an effort to create “Codes of Fair Competition” for all industrial sectors. That story is one of those that I often tell to make the connection between corporate history and the Great Depression. When it comes to trade associations the connection is even more direct—existing organizations were often put in charge of particular industry codes, and where one did not exist, they were often created with the blessing of the Roosevelt administration. Since the effort was ultimately pronounced unconstitutional it is little known today. Still, its historical consequences and its role in a corporate history can be profound. But you have to know to look for it.

A similar thing happened around the time of World War I. That conflict came at the end of what historians call the Progressive Era, a time of sustained reform that transformed America in countless ways. When I began researching the history of the Associated General Contractors of America, the official story was that President Wilson had personally asked contractors to form a trade association. But there was no evidence of that. One of my co-authors even searched the papers of Woodrow Wilson at the Library of Congress, but we never found an indication that this could be true. Instead we found a story that made much more sense—that the organization got its spark not from a war-weary president but from the United States Chamber of Commerce, itself the exemplar of Progressivism in the American business community.

And that, in the end, is the best reason to have a professional historian writing corporate history books. Your institution’s story does not simply stand alone—it is part of the complicated and endlessly fascinating sweep of the American story.

Contact me if you would like to talk about bringing new perspective to your corporate history book.

Public

Public