Authenticity in Anniversary History Books

In my thirty years of researching and writing anniversary history books there have been many moments of exhilaration; times when a discovery or new frame of reference either confirmed or confounded months of theories and assumptions. Some of the enjoyment comes from the thrill of the chase. But there is something more fundamental at work—these are landmarks in the pursuit of authenticity.

Anniversary history book projects usually begin with a few preliminary facts drawn from a Wikipedia article, sources provided by the client, or perhaps a newspaper article or two. They also begin with a received narrative. Nearly every company or organization has a timeline or a page or two of history that has been handed down for years. Seldom do all the pieces fit. There are bulges of detail here, thematically tight spots there, and places where the story thins and disappears. Like clothes off the rack you might have to force them to fit.

History insufficiently researched or incompletely drafted is by nature inauthentic. The story does not make sense or the overall account is too obviously contrived to convince. This is why the process of discovery is so gratifying. Every time you obtain a new piece of the story it helps you make sense of the old ones, every time you challenge and replace an old assumption with a new idea, you are making that fit a little better—you are getting closer to authenticity.

Most of these moments come during research, some follow naturally in the course of writing, but never until recently, writing the 200th anniversary history book for Acker, Merrall & Condit, once grocer, now wine auctioneer, have I had a nagging sense of the inauthentic dog me for nearly the entire length of the project. It was all due to the tradename, “Amcehat.” That was my Rosebud.

Setting the Perspective

Where to start in the search for authenticity in anniversary history? With Acker, Merrall & Condit, as with nearly all of my projects, I began my research in secondary sources. For some history projects, books are a beginning and an end. You could write a highly detailed and perfectly persuasive history of General Motors relying solely on the 174 histories of GM on the shelf at the Library of Congress. Historical consultants seldom have that luxury, they usually write about institutions that have little or no “literature.”

An early civil engineer’s handbook.

But books are still invaluable sources because they set the perspective and help you begin to think about your subject. For a recent anniversary history of the University of Delaware Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering I began by reading overviews of civil engineering in the United States to understand how to think about the profession. There were also a few histories of engineering education. Even though the institution that I would be writing about was never mentioned, these books helped me prepare for what I was going to encounter.

For the Acker anniversary book project I turned to a multivolume history of the wine business in America. Because I had started there and learned specifically about America’s sad addiction to sweet red wine between the 1930s and the 1970s, I knew what to expect and what to collect, when I moved in closer to the subject.

Having gotten a sense of perspective on the subject, you can then begin assembling a more detailed picture. The first step is usually newspaper research. When I started as a historian in the early 1990s plowing through papers was tough and time-consuming. Today, however, you can collect a complete set of articles from newspapers of record like the New York Times and Washington Post and local papers like the LA Times or the Boston Globe in just a few hours on a historical newspaper database. Many trade journals and second-tier newspapers and magazines are equally accessible in subscription databases.

Digging Deep

If you do not write history often, you may think after collecting several hundred articles that you have got the story nailed. I have learned otherwise. Newspaper accounts usually cover the outer shell of the institution that I want to describe. They detail things that the public were privy to—or more accurately things that journalists thought the public might care about. Top leadership, major triumphs, big mistakes, may all be identified. But the rank-and-file, the day-to-day, and what lay behind some of those ups and downs are usually left out.

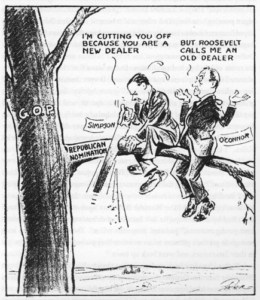

I was in an Egyptologist’s bedroom when I most fully realized how insufficient newspaper accounts could be. Dr. Kelly Simpson had hired me to write the biography of his father Kenneth Simpson, a now-obscure New York politician who was well-known and exhaustively covered in his day. In researching the biography eventually entitled Life of the Party I had collected and digested hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles ranging from accounts of local political club meetings to a lengthy New Yorker profile. I thought I knew my man.

Liberal Republican Kenneth F. Simpson was well-known in 1930s New York.

After about an hour working my way through the papers that Dr. Simpson kept in his bedroom closet, however, I encountered a cache of letters. Love letters. To and from a woman not Kenneth Simpson’s wife. It turned out that Simpson had a passionate, and horizon-expanding love affair, which his wife knew about, with literary critic Dorothy Dudley for 13 years. Suddenly a lot of things fell into place that had not quite fit before.

I may never experience anything like that moment again, but when I am digging deeper, I usually end up in the archives—any archives I can. Most of the Kenneth Simpson Papers had been left to Yale so I made sure to work through those. I also read the mail of his friends, politicians ranging from Thomas Dewey to Fiorello LaGuardia. Because other historians have told us much about those two, how they interacted with Simpson told me much about my subject.

With public figures it is easy to follow the archival trail. It is harder, but still feasible to do so with institutions as well. If the industry was regulated, then the appropriate agencies left records in the National Archives. If a company operated during wartime, then it interacted with government agencies that mobilized manpower and resources—and kept records. And if company managers were influential, wealthy, or perhaps just public spirited, their papers may have ended up at a university.

And then there is the internet. It is remarkable how much authentic primary material has been scanned and put online in recent decades. Since Acker, Merrall & Condit kept no archives, much of the most detailed research for my company anniversary history book was by necessity done on-line.

Photographs were a real problem. At one point, Acker was one of the largest luxury grocers in the United States. It was a New York City institution with dozens of stores. But neither the client, the newspapers, nor the editorial photo services could provide images of any of them.

But at some point, someone took an 800-plus page bound volume off the shelf of a library—Case Files of the New York State Supreme Court, 1905—and scanned them for Google. I had been trying various keyword combinations for months when that document came up in my browser. Buried deep within it were a few pages about an inconsequential lawsuit and an exhibit: a lengthy sales brochure full of photographs of Acker, Merrall & Condit stores circa 1900. It was another moment of exhilaration and suddenly my anniversary history book became much more authentic.

Staying with the Story

It is because of experiences like those described above that historians love doing research. Some amateurs and even academics never seem to get past that stage. A historical consultant needs to begin writing on schedule, however. But even then, the pursuit of authenticity should not stop.

Having done the research, reviewed the sources, and written the outlines, it is tempting to think that you know the story. Try writing it down. Inevitably those bumps and lumps start to appear. Even worse, the seams do not line up straight. Sometimes the research is thin, but it is equally likely that you have simply failed to think things through. Writing forces you to do that.

It is all too easy to cling to that received narrative that the client bestowed upon you months earlier. That was the case with a trade association history anniversary history book that I edited several years ago. The Professional Photographers of America (PPA) was formed in the mid-1800s. Since at least the late 19th century, PPA “historians” had been writing that the association was formed to fight a patent case, and that it did so and won.

The first draft conformed to that narrative. But it did not work. The organization had been formed in December 1868; documents indicated that the patent case had been closed in July 1868. For more than a century the cart had been before the horse—instead of forming the group and winning the case, the photographers had won the case and then formed the group. A small adjustment perhaps, but things like that make the difference between the authentic and the unconvincing.

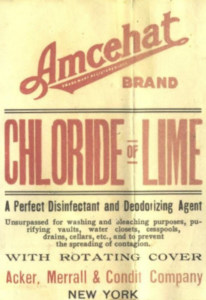

One of the unusual “AMCEHAT” labeled products sold by Acker Merrall & Condit at the turn of the last century. (Courtesy Montana Heritage Commission)

And finally there was my “Rosebud;” the time I nearly missed something that might have been lost forever. As I worked on my Acker Merrall & Condit anniversary history book, I wrote at length about the company’s nationally known house brand, “Amcehat.” This appeared to be an acronym, but of what? Inexplicably, nothing in the thousands of pages of evidence I had collected seemed to offer a clue.

After completing a sadly inauthentic chapter draft, I decided to sift once more. I found, deep in that sales brochure buried in the New York Supreme Court Records, a page with notice in its lower left-hand corner that read: “Amcehat: Acker Merrall Condit Eighteen Hundred And Twenty.” It was the first time that I had ever noticed anything like it. The company had made up a brand around its founding date—and then pretty much kept it a secret. I had missed this lone notice the first few times through the source because I had been so excited about the rare photographs. A small thing, perhaps, but no one is likely to write a history of that company ever again. Had I missed it, “Amcehat,” like the original “Rosebud” from the movie Citizen Kane, would have gone into the furnace unseen. In pursuing authenticity I had done my part for posterity.

Do you have a story yet to be discovered or corporate culture likely to be lost? Give me a call to discuss your anniversary history book.