Heroes, Historical Consulting, and Marquis James

The roots of historical consulting lie in the early to mid-20th century when corporations began to see their stories as an asset even as professional historians grew more specialized and less interested in institutions. Two biographers led the field. Alan Nevins attempted to craft compelling and contemporary history that met academic standards. Marquis James, on the other hand, favored more historically remote subjects and a more sensational approach.

Marquis James grew up in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the “Cherokee Strip,” the newly opened Oklahoma Indian lands where rapacity (toward both native Americans and less fortunate settlers) was part of daily life. In the 1910s James became a journalist, reaching the height of the profession in reporting on the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial” that pitted legends William Jennings Bryan against Clarence Darrow.

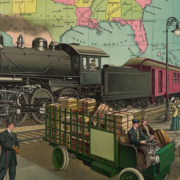

Then James began the work that had an immediate impact on American popular history, writing biographies of Sam Houston, Andrew Jackson, and John Nance Garner (Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice president). In these works, James demonstrated both an enduring strength: the ability to tell a good story; and fatal weakness: the tendency to see the heroic individual as the locomotive of history.

In 1941, in telling the life story of Alfred I. DuPont, James turned from political biography to business history. Two insurance company histories and books on Texaco and The Bank of America followed. James did meticulous research, but he invariably interpreted his sources to the credit of larger-than-life characters above all else.

This preference for the heroic made James a celebrated author in his day (he won two Pulitzer Prizes in the 1930s) and a forgotten one in ours. For in building up his heroes, James stripped away historical complexities, including the possibility that the bald-faced exploitation which American culture countenanced, and in which many of its legends participated, was anything but heroic.

It seems that at least one of Marquis James’s clients figured this out. In the late 1940s, J. Peter Grace, CEO of the chemical company that his grandfather had built by stripping Latin American countries of guano, commissioned a business biography of the founder. But when James completed the manuscript, Grace buried it, apparently realizing that documenting in admiring prose the exploitative underpinnings of the W. R. Grace & Company would undermine already fragile relations in Latin America. Merchant Adventurer: The Story of W. R. Grace did not see the light of day until 1993, a year after J. Peter Grace stepped down as CEO.

Today, historical consulting involves much more than the writing of books as it did in the days of Marquis James. And it also must involve much more than reflexively repackaging the one-dimensional legends and self-promotional stories that may have passed as history in an earlier day.

Public

Public